Officer Patrick Stevenson discovered a distressed bobcat near Mil Creek. But the animal wasn’t just injured and starving. It was guarding something. Clutched against its belly was a dirty white feed bag held in place with desperate trembling strength. After a tense, careful capture with the help of a wildlife rescue officer, they finally managed to secure the exhausted bobcat and remove the bag. It refused to surrender.

It wasn’t food. It wasn’t trash. Inside that torn bag was something that made both officers freeze in horror. What could make a wild animal guard something with its life? What secret had been hidden for 7 years? Stay with us because what started as a simple wild animal rescue quickly turns into one of the most beautiful wildlife stories you’ll ever hear.

Before we start, hit the like button and make sure to subscribe if you haven’t and hit that notification bell so that you won’t miss any new stories. That was the first thing Officer Patrick Stevenson noticed. It wasn’t the usual noise of his morning patrol, not the rumble of his cruiser’s engine on the gravel shoulder, not the distant chatter of the Dashes River, nor the cry of a redtailed hawk.

This was a sound that scraped against the peaceful Oregon dawn. It was a raw, guttural, repeating whale. It sounded to his weary 58-year-old ears like something caught between a baby’s scream and a cat’s desperate fight. He’d been a cop in the small town of Pine Ridge for 30 years. He knew the people. He knew the roads.

And he knew the sounds of the wilderness that pressed in on their quiet lives. This sound coming from the creek trail just ahead was one of pure, undiluted misery. Patrick pulled the cruiser over, the tires crunching on pine needles. He radioed in his position, his voice calm and practiced. Dispatch, this is Stevenson. I’m out at the Mill Creek trail head just off the 26.

Going to check on a Sounds like an animal in distress. Code one. He grabbed his heavyduty flashlight, though the morning light was already filtering through the massive ponderosa pines, and stepped out of the car. The air was cool and sharp with the scent of damp earth. The wailing sound was louder now, punctuated by furious, tearing hisses.

“Sheriff’s department,” he called out, a habit that felt foolish when dealing with an animal. He moved down the trail, his boots quiet on the packed dirt. He rounded a bend thick with wild roodendrrons and stopped dead. It wasn’t a dog. It wasn’t a coyote. 10 yard from him, huddled in a patch of tall, sunbleleached grass, was a bobcat.

It was a young male, but still a formidable creature. Its fur was matted with burrs and dirt, its tufted ears pinned back, its spotted body tense as a drawn bowring. Its ribs showed faintly, and its eyes, those intense yellow wild eyes, were fixed on him, but it was the whale that held him captive.

The animal would let out that terrible high-pitched sobbing cry, then lower its head and hiss. not at him, but at the thing it was guarding. Clutched between its front paws, pulled tight against its belly, was a dirty, crinkled white bag. It looked like an old, heavy plastic feed sack. The bobcat was draped over it, its claws hooked deep into the material, its entire body a shield.

Every few seconds, it would dip its head and rub its cheek against the bag as if comforting it before lifting its gaze back to Patrick and letting out another heart-wrenching cry. “Well, now,” Patrick murmured, keeping his hand away from his sidearm. “This wasn’t an aggression issue. This was something else. This was desperation.” He took one slow step closer. The bobcat exploded, not at him, but onto the bag.

It snarled, a sound like sandpaper on bone, and hooked its claws in deeper, pulling the bag so hard it tore slightly it was refusing to let go. It was guarding this piece of trash with its life. Patrick held up his hands, a placating gesture he knew the animal wouldn’t understand. Easy, fella. Easy now. I’m not I’m not going to take your whatever that is. He backed away slowly, his heart thumping.

This was above his pay grade. He was a town cop, skilled at handling speeders and the occasional domestic dispute. This was a job for someone else. He got back to his cruiser, the sound of the bobcat’s cries following him, more frantic now that it had seen a threat. He picked up his radio. Dispatch, get me Sarah Jenkins at Fish and Wildlife.

We’ve got a situation at the Creek Trail. A young bobcat looks to be in poor condition and it’s well, it’s got a hostage, a white bag, and it won’t let it go. 40 minutes later, Sarah Jenkins’s green wildlife and wreck truck pulled up. Sarah was half of Patrick’s age and had twice his energy, a nononsense woman with a biologist’s mind and a rehab’s heart.

She stepped out, already pulling on thick kevlar lined gloves. Morning, Pat. What’s the story? She asked, grabbing a long catch pole and a heavyduty transport crate. See for yourself, Patrick said, leading her down the trail. Been crying like that the whole time. Hasn’t moved, just guards the bag. Sarah stopped where Patrick had.

She observed, her eyes moving with professional speed. Yearling, she said quietly. Male, underweight, probably dehydrated. And you’re right. That’s distress. Pure distress. And the bag. Never seen anything like it, Sarah admitted. But look, she pointed around its neck. Is that a collar? Patrick squinted. She was right. Peeking through the matted fur was a thin dark line.

A simple worn leather collar. That’s not right. Patrick said a collared bobcat. Maybe a researchers, but it had no transmitter. No, this looked like a a pet collar. This just got complicated, Sarah said, her brow furrowing. He’s habituated, or at least he was.

That explains why he’s so close to the trail, but not why he’s starving or why he’s guarding that. So, what’s the plan? Patrick asked. Same as always, just trickier. We can’t leave him. He’s a danger to hikers, and he’s clearly not thriving. He needs capture and assessment, but he’s not giving up that bag without a fight. And I don’t want to tranquilize him if I can avoid it. His system is already stressed.

She unclipped the loop on the catch pole. Pat, I need you to be the distraction. Stand to my left. Talk to him. I’m going to try and come from the right. When I move, I move fast. The second I have him on the pole, I need you to get that bag. He’s going to fight for it. Do not let him hold on to it.

It could get tangled, hurt him, or he could hurt you trying to keep it. Patrick nodded, his mouth dry. He felt a deep, profound sadness for the animal. It was so human, this desperate clinging to a worthless object. “All right, fella,” Patrick said, moving slowly to the left, his voice a low rumble. We’re not here to hurt you. We’re just here to help.

You look like you could use a square meal. The bobcat’s head snapped between them, its whales turning to low, menacing growls. Its entire focus was on the two humans, but its paws never ever left the bag. “Now Sarah!” Patrick shouted, fainting a step forward. Sarah moved like a snake. In two quick strides, she was on the animal, the catchpole’s loop swinging.

The bobcat spun, hissing, but she was faster. The loop went over its head and neck, and she pulled it taut. The world exploded in feline fury. The bobcat thrashed, screaming, rolling, and flipping, its powerful back legs kicking. Sarah held firm, her knuckles white, bracing the pole against her hip, keeping the animals teeth and claws away from her. “The bag, Pat.

Get the bag!” she yelled over the den. Patrick moved in. The bobcat saw him coming for it and went berserk. It lunged, its body hitting the end of the pole’s cable with a sickening thud. Patrick grabbed the white plastic. It wouldn’t budge. The animals claws were hooked in like grappling hooks. “He won’t let go,” Patrick shouted.

“Pull! He’s exhausting himself!” Patrick planted his feet and yanked. The bag tore, but the bobcat’s grip held. He could feel the animals desperate, trembling strength. With a final, desperate twist, Patrick ripped the bag free. The moment it was gone, the fight stopped. As if a string had been cut, the bobcat collapsed onto the grass, its chest heaving.

The scream it let out was no longer one of fury, but of pure, devastating loss. It was a sound that would haunt Patrick Stevenson’s sleep for weeks. It was the sound of the very last thing in the world being taken away. Exhausted and defeated, it offered no more resistance as Sarah gently guided it, half dragged, half carried, into the transport crate and locked the door.

The sudden silence on the trail was deafening. Patrick and Sarah stood there, both breathing heavily. In the crate, the bobcat lay on its side, its yellow eyes wide, staring at nothing. Patrick looked down at the dirty white bag in his hand. It was heavier than it looked. “What on earth?” Sarah said, wiping sweat from her forehead. Could be so important.

Patrick pulled at the drawstring, which was knotted with mud. He worked it free and peered inside. His blood ran cold. Oh my god, he whispered. What? What is it? Sarah moved to his side. Patrick didn’t answer. He reached into the bag and pulled out a small frayed blue cat collar, then a red one, then a green one with a tiny tarnished bell.

He upended the bag and dozens of them spilled onto the pine needles. Worn, faded, and frayed cat collars. They stared at the pile, stunned into silence. It was a small mountain of tiny lost memories. Sarah, her face pale, knelt. “Look,” she said, her voice trembling. She picked up a small metal tag on one of the collars. It was handstamped. “01,” she picked up another 02.

Patrick looked from the pile of collars to the bobcat in the crate. He walked over and as gently as he could tilted the animal’s head to look at the collar it was wearing. It was simple brown leather. Attached to it was a small handstamped tag. It read 34. It wasn’t a gasp or a cry.

It was a shared, horrified, silent scream of understanding. “This bobcat hadn’t been guarding trash. It had been guarding graves.” “But why?” Patrick said, his voice thick. “Where did he get them?” Sarah was already examining the tags. “They’re all the same, numbered, and look on the back.” Patrick turned one over.

Stamped crudely into the metal were two initials and an address. A F and Route 4 Box 112. I know that place, Patrick said, his heart sinking. That’s Arthur Finnegan’s house just on the edge of town, bordering the forest. The town catman, Sarah said, her expression hardening with a dawning terrible realization. Pat, I’ll take the bobcat to the holding center for assessment.

You You go talk to Mr. Finnegan. I think he has a lot to answer for. Patrick drove to the small house on Route 4. The bag of collars sitting heavy on the passenger seat. The smell that wafted from it was faint, a musky, dusty, feline scent. The scent of years. Arthur Finnegan’s house was small, tidy, and quiet.

The only sign of its inhabitants was the halfozen clean water bowls on the porch and the faint, not unpleasant smell of pine pellet cat litter Patrick had known Arthur for years. in the way everyone in a small town knows each other. A quiet man, a widowerower, kept to himself. He was known for taking in the strays no one else would touch. The oneeyed, the three-legged, the old, and the feral.

Patrick knocked on the screen door. Mr. Finnegan, Arthur, it’s Officer Stevenson. A moment later, the inner door opened. Arthur Finnegan stood there, a tall, painfully thin man in his late 70s with kind, watery blue eyes and a face etched with a lifetime of quiet worry.

Patrick, is is everything all right? Hello, Arthur. Can I come in for a minute? I need to ask you about about an animal. Arthur’s face pald. He held the screen door open. Of course, the house was immaculate. A few domestic cats, a sleek black one, an orange tabby, watched Patrick from the safety of a sofa before vanishing into the back rooms.

“Please sit,” Arthur said, gesturing to a worn armchair. Patrick remained standing. He couldn’t bring himself to get comfortable. He held up the white feed bag. Arthur, we found this down by the creek trail this morning. Arthur’s eyes fixed on the bag and his entire body went rigid. A hand flew to his mouth and a small choked sound escaped him.

“Oh, oh no,” he whispered. “He’s you found him? Is he all right? He’s been gone two days. I I thought he’d just gone for good this time. He’s safe, Arthur, Patrick said gently. But he’s he’s a bobcat, and he was guarding this bag with his life. Patrick emptied the collars onto the coffee table. The little bells tinkled.

Arthur Finnegan sank into his chair, his face in his hands. He began to cry, not loudly, but with the deep, racking sobs of a man who had held in a secret for too long. “I never meant to,” he whispered, his voice muffled. “I swear, Patrick. I never meant for it to happen.” Patrick sat down opposite him. “Tell me, Arthur. Tell me what happened.

” Arthur took a long shuddering breath and wiped his eyes on his flannel sleeve. It was it must be 7 years ago now. Just after my merry passed, the house was so empty. I started, you know, taking in the strays, the ones from the feed store, the ones dumped at the landfill. It gave me a purpose. He looked at the pile of collars, his gaze distant.

One night, there was a terrible storm, a spring thunderstorm. I heard me out by the wood pile. It was a litter. Four of them. Their mother was She’d been hit on the road. He paused, gathering himself. I brought them in. They were so small, their eyes barely open. I bottlefed them. Three were just, you know, tabies. But the fourth, he was different.

He was spotted. And he had these these funny little tufts on his ears. And his paws, my goodness, his paws were so big. I I’m an old man, Patrick. I’m not a fool, but I think I wanted to be fooled. I told myself he was a a main mix. Something exotic someone had dumped. He was just a kitten, a tiny helpless thing.

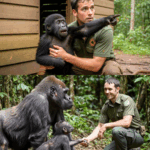

What was I supposed to do? Leave him? So you raised him? Patrick said, his voice soft. I raised him, Arthur nodded. I called him Boots. He grew up right alongside the others. He He thought he was a cat, Patrick. He truly did. He’d sleep in a pile with the others. He’d He’d try to purr this deep rumbling sound. He’d rub against my legs for breakfast. He He was my boy.

And the collars, Arthur. Patrick gestured to the table. Arthur reached out and touched a small red one. my my box of memories when when one of them passes. It’s the hardest part, you know. They don’t live long enough. I I can’t bear to just throw them away. So, I keep their collar, a little a little piece of them. I put them in that old feed bag.

It’s It’s all of them. All the ones I’ve loved. and and lost. It sits on the back porch. He looked up, his blue eyes swimming with tears. Boots. He was always different. He knew he’d sit with me when one of them was sick. He’d just watch. And when they were gone, he’d grieve. He’d pace. He’d cry. He understood. A piece clicked in Patrick’s mind.

Arthur, did you lose one recently? Arthur’s face crumpled again. Last week, my patches, an old calico, she was she was one of the first. She’d been with me 15 years. She and Boots, they were inseparable. She was the one who who motherthered him when he was a kitten. They slept together every single night. She She passed in her sleep right next to him.

Now it all made sense. The terrible wrenching truth of it. I buried her out by the old oak, Arthur continued, his voice barely audible. And Boots. He just He wasn’t right. He wouldn’t eat. He just paced the house wailing that same sound you must have heard. He’d go to the back porch and just sit staring at the bag. He He knew.

He knew she was in there. That they all were. Two days ago, Arthur whispered, “I woke up and he was gone. And the bag, the bag was gone with him. He didn’t just run away, Patrick. He He took his family with him. He was He was looking for patches. He was clinging to the only thing he had left of her, of any of them.

Patrick Stevenson, a 30-year veteran of the Force, a man who had seen the worst of people, felt a tear trace a line down his own weathered cheek. He quietly reached out and placed his hand on the old man’s shoulder. Sarah Jenkins met them at the holding facility. She had listened to Patrick’s story over the phone, her voice tight with emotion.

When Arthur stepped out of the cruiser, she didn’t treat him like a man who had broken the law by harboring a wild animal. She treated him like a man who was grieving. “Mr. Finnegan,” she said softly. “He’s in here. He’s safe. He’s sleeping.” The vet gave him a mild seditive and some fluids. He was he was exhausted, utterly spent.

She led him into a quiet climate controlled room. There in a large recovery enclosure was the bobcat. He was asleep on a soft blanket, his breathing deep and even. He looked smaller, more vulnerable without his wild fury. He’s beautiful, isn’t he? Arthur said, his hand on the mesh. He was always so beautiful.

Arthur, Sarah said, her voice gentle but firm. We have to talk about what happens now. You, you know, he can’t come back to your home. Arthur didn’t look away from the sleeping animal. I’ve I’ve known this day was coming for seven years, dear. Every time he looked at a deer in the yard, every time he’d make that chuffing sound, I knew I knew he wasn’t a cat.

I was I was just a lonely old man being selfish. I didn’t want him to be alone. and I didn’t want to be alone. You gave him 7 years of love he never would have had. Sarah said he would have died in that storm. You saved him, Arthur. But now we have to save him again. He can’t be put down. Arthur’s voice cracked. Absolutely not, Sarah said, her voice fierce. No, he’s not aggressive.

He’s He’s confused. He’s imprinted. He can’t be released into the wild. He wouldn’t survive. But I know a place, a wonderful place, a licensed wildlife sanctuary up in the high desert. It’s not a zoo. It’s It’s a home for animals like him, ones that are caught between two worlds. He’ll have room. He’ll have acres to roam in a natural enclosure.

He’ll He’ll see others of his kind. He can He can finally learn how to be a bobcat. Arthur finally turned, his eyes searching hers. “Will he be happy?” “He’ll be cared for,” Sarah said. “He’ll be safe and he’ll be understood.” I think I think that’s the best we can do for him. Arthur Finnegan nodded a single slow painful gesture.

All right. All right. It’s It’s what’s right. It’s what’s right for him. He had one last request. He took the bag of collars from Patrick. He walked over to the enclosure and set the bag down just inside the mesh near the sleeping animals head. Just just so he knows he’s not alone, he whispered until he gets there. A week passed, a long, quiet week.

Arthur’s house felt emptier than it had in years. Sarah had called to say the bobcat, whom the sanctuary had simply named number 34, had arrived safely and was settling into his quarantine enclosure. “Then on a bright, cold Tuesday, Sarah’s green truck pulled into his driveway.

“He’s ready for a visitor, Arthur,” she said, smiling. “If you’re up for the drive.” The drive was 2 hours up into the high desert, a land of juniper, sagebrush, and vast open skies. The sanctuary was hidden away, a series of massive chainlink enclosures that blended seamlessly into the rocky landscape. It was quiet, peaceful. The director, a woman named Dr.

Eva Rusta, met them. He’s in his main enclosure now,” she said, shaking Arthur’s hand. “He’s remarkable, very cautious, very gentle, and he’s fascinated by the other bobcats in the neighboring enclosures.” She led them down a path to an enclosure that must have been 3 acres filled with rocks, old growth juniper, and patches of sunlight. At first, Arthur didn’t see him. He’s on the high rock, Dr.

Rostova pointed. His favorite spot. And there he was. He was magnificent. His fur, clean and brushed by the wind, was thick and bright. His muscles were lean. He looked wild. He looked like he belonged. Arthur walked slowly to the fence. He didn’t call Boots. That name was for a different animal, a different life. He just stood and watched.

For a long minute, the bobcat didn’t move. He was staring out over the desert. Then his tufted ears swiveled. He turned his head. He looked down. He saw the old man standing by the fence. He stood up, not in alarm, but in recognition. He was a hundred yard away. Slowly, deliberately, the bobcat began to walk.

He moved with a live, powerful grace that Arthur had never seen on his back porch. He didn’t run. He just came. He stopped a foot from the fence, his yellow eyes locking with Arthur’s blue ones. He was no longer a confused, grieving animal. He was a bobcat, confident, calm.

“Hello, boy,” Arthur whispered, his hand resting on the chain link. The bobcat looked at him. He made no sound for a long moment. Then he let out a low, soft chuff. It was the sound he used to make all those years ago when he wanted his breakfast. He stepped forward right to the fence. He turned his head and for one brief perfect second pressed his broad forehead against the wire right where Arthur’s fingers were.

It wasn’t a cat’s headbutt. It was a a gesture, a quiet, knowing final acknowledgement. Then he stepped back. He looked at Arthur for one more second, turned, and with a powerful, effortless bound leaped up the rock face, disappearing over the top. Arthur Finnegan stood there, tears streaming down his face.

But this time, they were not tears of sorrow. Sarah put her hand on his shoulder. “He’s all right,” Arthur whispered, his eyes on the empty rock. He’s home. He’s finally. He’s finally home. He stepped back from the fence, taking one last look at the wild, beautiful space that now held a piece of his heart. He had lost his strange wild cat.

But he had finally truly given him the one thing his love never could, the world. [Music]

News

Black Woman CEO Told To “Wait Outside”–1 Minutes Later, She Fired The Entire Management

Lieutenant Sarah Chen had always been good at blending in. At 5’4 and weighing barely 125 lbs, she didn’t look…

Five recruits cornered her in the mess hall — thirty seconds later, they learned she was a Navy SEAL

Lieutenant Sarah Chen had always been good at blending in. At 5’4 and weighing barely 125 lbs, she didn’t look…

Officer and His K9 Found Two Children Bound in the Snow — What the Boy Whispered Left Him Frozen

Officer Adam Smith thought he’d seen it all until that night in Silver Creek. The blizzard was raging when his…

Black Belt Asked Her To Fight As A Joke – What She Did Next Silenced The Whole Gym

They laughed when she walked in with her mop. Did the cleaning lady come to watch martial arts, too? A…

Twin Black Girls Kicked from Flight No Reason — One Call to Their CEO Dad Shut Down the Airline!

I don’t know how you people managed to sneak into first class, but this ends now. Flight attendant Cheryl Williams…

The police officer said a black woman — Seconds later, she said, “I’m the new Chief of Police.”

is locked onto Torres with an unsettling calm. “No tears, no anger, just a quiet intensity that made the air…

End of content

No more pages to load